THE ANCIENT PARISH CHURCH OF RUNCORN

Bert Starkey

Runcorn is an ancient town. Its foundation dates back to 914 when Princess Ethelfleda built a fort at the narrows of the River Mersey in order to prevent Norse long ships from passing up the river. A settlement was established to support the garrison and the hamlet would require a church which was almost certainly built of wood. This would be replaced by stone during the Norman period. Over the following centuries the parish of Runcorn came into being. Its boundaries stretched to include Thelwall, Daresbury, Aston and Halton, making it a remarkably large parish. In these places chapels of ease were built to accommodate those parishioners who lived at a distance from the mother church in Runcorn. Each chapelry had a curate or priest in charge. A curate today is a young man starting out in his ministry, but a curate in times past could be up to 70 years of age. The congregations of the chapels were required to contribute to the upkeep of the Runcorn church. They had to pay towards its repair. They had to contribute towards the cost of the fencing, the gates, the stiles, and the bell ropes at Runcorn. The chapelries even had to pay a share of the costs of the candles, the communion bread and the wine used at the Runcorn church, and there were constant disputes between the Runcorn church wardens and the chapel wardens over money all the time right through the centuries.

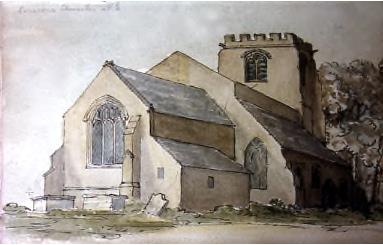

This is the ancient parish church from a water colour of 1820. It’s a view from the north-east. If you are walking along Mersey Road towards the bridge this is the view you would have. The architecture is about 1240; it’s Early English period. It was originally the church of St Bertelin, an obscure Mercian saint from Derbyshire in the late 9th century. At an unknown date it became St Bartholomew’s and then in the 19th century the new church became All Saints. By 1800 this old church was in a terrible condition. Much of the building was 600 years old. It was shoddily built and alterations and poor repairs had affected the very stability of the church. The tower had a dangerous overhang, the mortar was perished and the masonry was loose. But, in spite of its precarious state, the tower could not be taken down because this would bring about the complete collapse of the church. By 1820 the tower was so unsafe the bells couldn’t be rung and the only way of announcing services was by pulling on a cord that was attached to the clapper on one of the bells. Repairs to north aisle seen here could not be carried out because if the roof were to be removed the walls would fall - this was the opinion of the architects. The roofing slabs were porous and they were three times the weight of the roofing slabs on the south side.

At the time of its demolition in 1846 the east window still retained some fragments of ancient glass. All the other coloured glass had been smashed out at the Reformation or during the parliamentarian rule during the Civil War. This was done to ‘let in God’s heavenly light’. This happened all over England; symbols of Catholic practice were removed, including statues, wall paintings, carvings and altars. At Runcorn, one statue remained, and that was in the west side of the tower, and of course the gargoyles remained on the tower until its demolition. The Brookes of Norton had almost made the chancel their private chapel. The chancel was the only part of the church that was in good repair because the Brookes had made it their own. They buried their family members there and they had used it since the 1540s. In 1802 the church was extended by the addition of an enlarged south aisle on the far side of the church. This did little to improve the comfort of the church. It was a still overcrowded and the congregation grew very quickly in the early years of the 19th century. By 1830 the Vestry resolved to demolish the building and build its replacement on the same site and the last service was held in this church in September 1846. Little could be salvaged, but the bell metal was valuable. It had a ring of five bells and these were sent to the foundry as part payment for the costs of a new peal of bells for the new church of eight bells. One of the bells was sent to Holy Trinity church where it is still in the tower (it is not rung now because it would be unsafe to do so). Divine services were held in the National School, as the parish school was called, until the new church was ready. All Saints church was opened in January 1849. The new church cost £8,052 and it had seating for 1,060 parishioners. And yet the parish magazine recalls in Victorian times that the church warden had to force people away because the church was so full at harvest festival. On a couple of occasions they couldn’t all get in, yet the building held well over 1,000. From a little village, Runcorn had grown to a large town and as the church could not accommodate the growing congregation, another larger church would soon be required. It had been the centre of the community for centuries, the only substantial building at one time in the whole town. It was isolated at the end of Church Lane, now Church Street, and the vicarage house was always a mile away in Higher Runcorn in Highlands Road. In Victorian times new churches were being built all over Britain and ancient buildings were being ‘restored’.

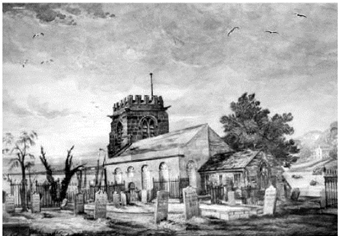

This is a view of the church from the south side. It was painted in 1846, the year it was demolished: the artist actually wrote on a gravestone “Runcorn Church 1846’. This picture came from the Isle of Man. How it got there I don’t know, but you can see the round-headed windows on the south side; they are like a non-conformist chapel. This is the new aisle added in 1802. There are no photographs of this building although it was there just at the birth of photography in the 1840s. When the church was taken down it was found that this part, this southern aspect here, which was 40 years old, was in worse condition than the church which was 600 years old. Jerry building you see - no funds.

This is an enlargement of the gravestone with the artist’s name on it and you can just about see there the date of 1846.

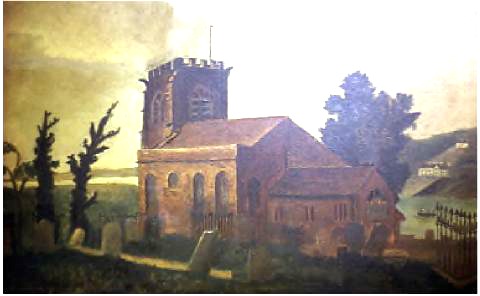

This is an amateur painting from the same spot in Church Lane (now Church Street). You can see the modern work there and you can see the ferry going across to Widnes and the Mersey Hotel, as it is now called, is there. There were a lot of trees around the church at one time, particularly massive yew trees,trees that four men couldn’t span round; 800 years old when the church was demolished. If you want to appreciate the size of one of them (they are not here now of course) there is one in the churchyard at Eastham. They were not very tall but were of enormous girth. Widnes, as you see was then entirely rural - nothing there, no industry, no houses; in the distance you might just see a farm building, or the windmill at Bold but nothing else.

Looking down river the church was embosomed in noble trees. Notice the ferry hut, you’ve often heard people talk of the ferry hut, well there it is. The ferry gear was kept there. Then there is a bridge, Castle Bridge. It spans a channel across the Duke’s Gut. The Duke’s Gut was a channel cut across Runcorn promontory in order to channel the ebb tides through to his canal so that the tide would scour away the mud and the sand which tended to accumulate. A few years earlier the ferry didn’t leave from here. It left from behind the Boat House Inn, hence the name ‘Boat House’, a quarter of a mile upstream. The Old Quay Company and the Trustees of the Duke of Bridgewater took over the pool and an observer noted ‘the town was therefore excluded from the said creek, which some persons complain against’, and a new landing place was made near to the church. These trees were cut down around the same time as the church was demolished, which led to uproar in the town. I think this little vessel here is a Mersey flat, or a type which developed into a Mersey flat; a square-sterned little boat for working on the river. These pictures were painted by Mr Allen, who was curate at the Parish Church in the 1820s. He had a book which was called ‘Greswell’s History of Runcorn’ which was written in 1803. There were no pictures in it, but Mr Allen was a talented water colour artist and he painted these pictures and he put them in the book.

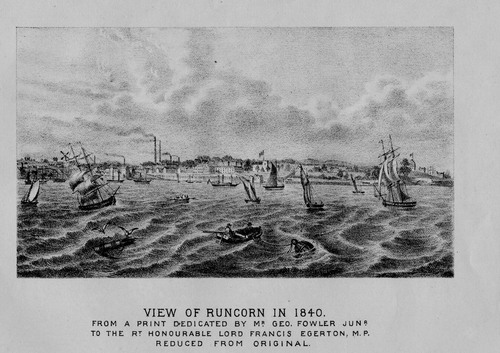

Another view of the church, a few years on, the windmill on Delph Bridge is there. That will lose its sails in about 1850 and will be made redundant by the steam mill, which is on the water edge there. There are the salt water baths, because Runcorn was then a spa town and people came for the good of their health. They came to take the air. There were boarding schools established for the children of rich merchants who wanted to their children to go to school in an area that was more salubrious than Liverpool or Manchester and, of course, the views down the river where then superb. The river was indeed a notable salmon run. In fact, there were sturgeon on occasion coming up. This is Runcorn in transition. In forty years, from 1830 to 1870 it was transformed from a quiet little sleepy village into a very bustling sooty industrial town. The beginnings of change!

Here you see the first factory chimneys appearing and steam boats on the river, but there are still bathers in the clear water. Here is the Gut, and Castle Bridge and parkland are seen. That’s where you will find South Bank Terrace now, Collier Street, Lord Street and Blantyre Street. There is the church and there are the factory chimneys. The Gut didn’t always function satisfactorily, but when it did it could pull small craft into its millrace and be very dangerous. Another 30 years would bring about great changes. By 1870 the old church had gone and by 1868 the railway bridge was built. The picturesque waterfront would be swept away with the coming of the Manchester Ship Canal. There would be no bathers then and the bath house was pulled down and Castle Bridge disappeared. So, 40 years could make tremendous change in that scene there.

This picture is taken from Nickson’s ‘History of Runcorn’. The old church is somewhat insignificant. There it is under the flag and the factory chimneys are very much in evidence.

Here we have a picture after 1849; the new church is in position, the seaside boarding houses, Belvedere and Clarence Terrace are still there, the factory chimneys are in evidence, the windmill too, and quite a lot of shipping on the river. I understand that craft coming to the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal had to pass the canal and come some way up river precisely at high tide and turn and go into the dock. I don’t know why that was the case, but that was what I heard. The factory chimneys are tall; they have to be because by now they are making chemicals, alkali, by primitive processes and sending out fumes that caused havoc to farmland.

This is a view looking down the river; it is another one of Mr Allen’s watercolours. The flats were probably carrying coal from the Sankey Canal to Liverpool. In the 1800s there were hundreds of these handy little crafts working to Warrington, Northwich, Runcorn, and later to Widnes West Bank dock. They made a picturesque scene. As you can see there were so many of them it looked like a regatta. Notice the beehive structure there on the shoreline, on the end of that pier there. It’s probably a little beacon to aid navigation by night.

The Interior of the Old Church. In the chancel there is a foreshortened view of a flag. That is the flag of the militia, the Loyal Runcorn and Weston Volunteer Infantry, a militia that came into being during the Napoleonic war. When the new church came there was no place for the old flag and they used it as a floor cloth,which was a

great shame. You can see the three-decker pulpit here - more about that later. The box pews; at one time every church in England had these. They were probably carved with the names of parishioners going back for centuries. The Royal Coat of Arms, George III, it still exists, salvaged, and there is a table of benefactors at the back of the church - givers who had contributed towards the church, or “to the improving of the ways”, the mending of the roads. Their names were put on boards at the back of the church. That is still there. Many of the plaques removed from the old church, the marbles commemorating the Brooke family, and those in memory of former vicars have been retained for the new church. They are not seen here, but All Saints possesses very valuable communion vessels from

Elizabethan times, silver flagons and a paten dating back to 1670, an old altar chair and an oak table

that was formerly a communion table, given by Sir Richard Brooke. The feature that is most

interesting is the rood screen. The rood screen was a principal feature of every church and probably the

most attractive thing in the church. When the church was pulled down somebody with a heart saved

fragments of the intricate carvings of the screen and they have been fitted into the backs of the modern

pews. You can see here the early English arches, 1240 I would think, and the modern cast iron

columns of 1802. There was also, at one time, a sounding board to the pulpit. Out of vision almost are

the altar rails, wooden altar rails that I am trying to trace. They still exist in a church in Wales.

When the church was demolished in 1846 Thomas Hazlehurst, the soap manufacturer, bought the pulpit and presented it to the Methodist Chapel in Beaconsfield Road in Widnes. It was moved, yet again, to the new Methodist Chapel in Derby Road, Widnes, and is still in use today. The door still squeaks after centuries and here it is, highly polished, in Farnworth Methodist Church.

When the church was demolished in 1846 Thomas Hazlehurst, the soap manufacturer, bought the pulpit and presented it to the Methodist Chapel in Beaconsfield Road in Widnes. It was moved, yet again, to the new Methodist Chapel in Derby Road, Widnes, and is still in use today. The door still squeaks after centuries and here it is, highly polished, in Farnworth Methodist Church.

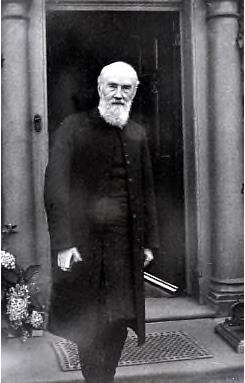

This is Canon John Barclay, who was born in York on Christmas Day in 1815. He was the vicar of Runcorn from 1845 to 1886, 41 years. He succeeded Mr Master who was the turbulent priest who had a rough time. Mr Barclay saw the parish through the difficult years immediately after the demolition of the old church. He was much respected by all Runcornians.

He wanted education for all. He was responsible for St Peter’s Mission in Dukesfield. Mr Barclay encouraged the Church Friendly Society, Runcorn Parish Penny Bank, and he was chaplain to the local Cheshire Volunteer Rifles. He saw the creation of St Michael’s in Greenway Road and the school in Shaw Street. He was an excellent preacher and was extremely well thought of. He was a former tutor of Greek and Roman history at university, and yet he gave all this up to a poor place like Runcorn. A comfortable life in Oxford he could have had, but no, he served his time, spent his life here. His gravestone is the only upright one still standing in the Parish churchyard. A few years ago, some hero painted a swastika on it, and the vicar at the time sensibly refused to use a solvent to remove it, he said “No, let the weather do that, it won’t damage the stone” and it is gradually disappearing. So, if you want to find his grave it is against the door of the church, just to the right of the door. Canon Barclay may still have a presence in the church, because on the springing of one of the arches, the vestry arch, there is a carving of a clergyman wearing a traditional Canterbury cap and the stone clergyman also has a hairstyle similar to that worn by Canon Barclay. On the other side of the arch there is the head of a lady, a stone carving of a lady, and we think that may be of Matilda, his wife. It’s not proven, but it would be nice to think so. So, maybe he is still there!

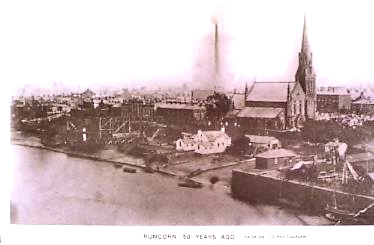

Runcorn about 130 years ago, around 1875 We can see a lot of detail in this. The windmill tower is still there, though the sails have gone. The factory chimneys are astonishingly tall; the fumes even burned up the crops on the other side of Norton. The soapworks were making chemicals by this time. The church instead of being a glorious pink is now black, a uniform black. The saltwater swimming baths are not used any more. The ferry boat across the river is at the end of the walk here. There is a boat being repaired, or being built, at Blundell and Mason’s shipyard at Belvedere, and all together it is a very black town. Some buildings still exist now of course; the minor Georgian terrace opposite the church still exists and so do the cottages here. Clarence Terrace still exists, but Belvedere has gone. What 40 years does, what industry does to an area! This photograph is taken from the railway bridge before the building of the Manchester Ship Canal and the church dominates the waterfront as you see. Nathaniel Hawthorne, the famous American writer, visited Runcorn in 1863. He was not impressed and he wrote: “A meagre, uninteresting, shabby built brick town with irregular streets. Not village-like, but paved and looking like a dwarf stunted city”.

All Saints churchyard is now a pleasant garden. I had a conversation with a workman who was laying gravestones to be made into paths in 1963. He told me that when levelling the ground his bulldozer unearthed the skeletons of scores of children buried a foot or so below the surface. In times past child mortality was appalling, unbelievable. Even into the early 20th century it was, as you can see by looking at the parish magazine of All Saints, but in any town parish it was the same. To explain what had happened; bereaved parents would slip the sexton a sixpence and he would bury a little bundle in some disused part of the churchyard. Although the bulldozer didn’t go down more than a foot this is what it turned up, very sad. The Victorian directories at the time stated that All Saints graveyard had an immense accumulation of upright gravestones. One of the points of dispute between Mr Master and his Vestries was his insistence that he wanted to decide where burials could take place. They wanted to be buried with family members, but he didn’t want to allow that and we know why. In Mr Masters’ day the churchyard was very small, it was God’s acre and it was little more than an acre. The ground had been used for burials for 1,000 years. In medieval times it was used for markets and fairs and open air celebrations. One vicar in the 16th century was warned by the Bishop for keeping sheep in the churchyard. There was no other consecrated, or hallowed, ground anywhere near the town. There was some at Aston after 1630 and there was a Quaker burial ground near Kingsley, Newton-by-Frodsham. So, in the early 1800s crowded town churchyards were vile beyond description. A burial, say in 1830, would often result in the unearthing of parishioners long departed, but sometimes the fairly recently dead, in a repulsive state, would be exhumed. The ground was used over and over: ‘Alas poor Yorik’, you remember him in Hamlet. The Bronte sisters had to keep the windows of their Howarth parsonage closed because of the stench from the churchyard. We can understand from Mr Master why he intended to have the last say in the place of burial. His dispute with the Vestry was bitter and, of course, paupers’ graves could be really offensive. There was a phenomenon; there were ghosts. Now, this is a serious lecture, but there were ghosts in the parish churchyard. It was a phenomenon called ‘corpse candle’, a fluorescent flame shape seen above recently made shallow graves – Arthur Mee’s encyclopaedia; I remember it from my youth. No wonder the church was in isolation at the end of Church Lane and the vicarage was a mile away!

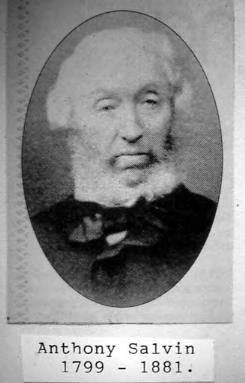

Anthony Slavin, the architect who designed All Saints. He restored and built many castles for the aristocracy. The best known were his country houses. He built 25 churches and restored many more. He designed Peckforton Castle near Beeston, a medieval fortress that Lord Tollemache required because he believed that one day the lower orders would rise up against him as the French peasantry had done in France in the revolution. He was going to be ready, so he built a fortress in the 1840s. Salvin designed the chapel at Arley Hall, and he restored Weaverham church. He was very famous; he carried out work on Windsor Castle and the Tower of London, Norwich Cathedral and Alnwick Castle. So you see, Runcorn is now a wealthier place, because there was money about, they could afford a good architect and they can build a splendid church.

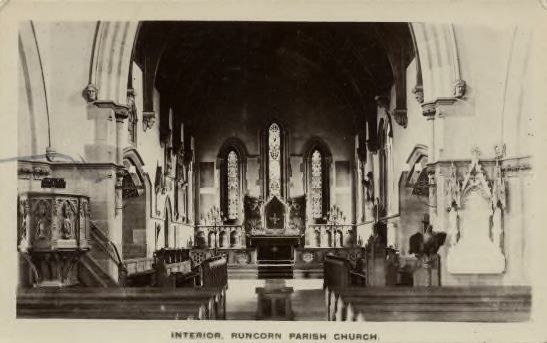

This is the interior of the modern church, built in the same style as the old one, with Early English pointed arches. It’s not my favourite style, I like perpendicular better and Romanesque even better than that, but these pointed arches were in vogue at the time, with lancet windows at the far end, like the old churches, I say, Neo-gothic, new Gothic. Salvin’s designs were not entirely satisfactory because the chancel was too dark in winter mornings and you had to put the gas on during services. So, in 1900 they pierced through the wall arcading on the south side and made lancet windows and this gave a much brighter interior to the church. The windows you can see down the end were given by Sir Richard Brooke.

Another view of the chancel, a closer view of the chancel, a much happier picture. In 1900 Miss Barclay presented new alabaster rails in memory of her father. She also gave a fine marble reredos, at the back there. The floor of the chancel has magnificent Minton encaustic tiles inlaid with different coloured clay. Runcorn Town Hall and St Mary’s Church, Halton, also have these wonderful floorings of Minton tiles. At Halton, it is said, they are so valuable that the Victoria and Albert Museum recommended that they be covered with carpet to protect them, so you can’t see them; they are gone. You can see them in the Town Hall. These buildings were built within two years of each other, St Mary’s, the Town Hall and All Saints. The chancel has many commemorative marbles to members of the Brooke family and the chapel on the south side is a chapel to commemorate the 67 old boys of the parish school who were killed during the First World War who were parishioners at the church.

This is the detail from the ancient rood screen. It is one of Roy Gough’s pictures. The designs are 15th century, in a perpendicular style and there are 20 different patterns and they are very handsome. A man named Fred Crossley was the authority on church furnishings and he wrote enthusiastically about these at Runcorn. He said that these are of Welsh influence, but I don’t know what he means, apparently church screens still in existence in Wales are very much like that. But, the destruction of the screen was a tragedy; it was a really attractive feature.

This picture is my effort taken to show to the children in my class some years ago, taken at the end of the harvest festival.

The vicarage was always situated away from the church in Highlands Road. A report of 1778 tells us that the house was in a dilapidated condition. It was, like the church, a patched up building. It was a very poor parish; there was never any money to pay for major alterations for the essential repairs, little comfort for the vicar or his incumbent in those days.

This picture shows parishioners outside the old Georgian vicarage in the early years of the 20th century. It was in poor condition because in 1800 when it was built Vicar Keyt paid for much of the cost out of his own pocket so much of it was a Jerry built building. The modern house, the next vicarage, stood on the same spot.

Vicar Howard Perrin, later Canon Perrin, built a new house in 1912. At last the clergy and their families

have some degree of comfort. The vicarage was sold some years ago. I was once thrown out of there you know. The vicar asked me along to do some research and I was sat there when his wife came along and chivvied me out. She wanted to do some cooking. There is some mysterious lettering on the garden wall at the vicarage - possibly the work of the Reverend Doctor Free, who was the vicar of Runcorn in the early years of the 18th century. He

is known to have carved the Latin inscription on a viewing point above Weston Point and he was something of a poet. By the way, I am interested in Dr Free because he entered into very lively correspondence with John Wesley, who came into the Runcorn parish. Runcorn parish was very big and Doctor Free didn’t like this at all and they corresponded with some venom. But, 25 years after Doctor Free had left the area John Wesley was still coming

to Runcorn parish and taking part in open air preaching. I’m told that the carving has now disappeared.

The Hearse House, now an electricity sub-station; my picture taken over 50 years ago. It’s equipped with a stove to keep the harness free from mildew and the hearse. All Saints churchyard of course was undenominational. If you look on the gravestones you will find Methodist ministers buried there and you will find Welsh Congregation ministers also buried there.

This is a document from 1776 stating the conditions to be observed by anyone using the hearse. There are four signatures on this document, the first one is James Starkey, and the third one is Peter Johnson.

Canon Barclay’s memorial is in the church. He was vicar of Runcorn for 42 years. It is there for you to look at; you can see the flowing hairstyle, note the Canterbury Cap.

The Alcock memorial. Thomas Alcock was the vicar of Runcorn for 42 years, but he was a pluralist because he was also the vicar of St. Budeaux in Plymouth. He much preferred his Devon living and he rarely visited Runcorn. He left All Saints parish in the hands of a succession of curates. He was a wealthy man. He married twice and on each occasion he inherited a fortune.

The marble records Nathan Alcock, his brother, who was a famous doctor, nationally known for his skill. He was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He retired to live in Runcorn. A third brother, Matthew,owned much of Runcorn. The area now covered by Runcorn cemetery, from Greenway Road down to Heath Road, was in the ownership of Matthew Alcock. The Reverend Thomas Alcock’s fortune came back to Runcorn; it was eventually inherited by the Johnson family, the soap manufacturing family, and the Orred family, who became principal landowners in Weston and Runcorn.

.jpg) As a short-term problem to the crowded churchyard, some land to the west of the church, towards today’s Waterloo

Road, was bought in 1833. New iron gates and railings were installed. They are now 173 years old. They are

weathered, but are still satisfactory, look at them, they are really massively made. The new extension, of course, was

very small and within a few years even that was filled and the new town cemetery was essential. Look at today’s

South Bank Hotel, which was also built in the Neo-gothic style for Dennis Brundrit the ship builder and quarry

master. He was a staunch Anglican and yet his eldest son became a Roman Catholic priest. Dennis Brundrit’s house is surrounded by gardens and there was a large orchard. In 1850 there were three large houses in the vicinity; Mr Cooper’s Grove House, Charles Hazlehurst’s Waterloo House and Dennis Brundrit’s house. Grove House has a Victorian front on it now, but you can see evidence of Georgian work on it. They were like three riverside villas on a country lane, how times have changed!

As a short-term problem to the crowded churchyard, some land to the west of the church, towards today’s Waterloo

Road, was bought in 1833. New iron gates and railings were installed. They are now 173 years old. They are

weathered, but are still satisfactory, look at them, they are really massively made. The new extension, of course, was

very small and within a few years even that was filled and the new town cemetery was essential. Look at today’s

South Bank Hotel, which was also built in the Neo-gothic style for Dennis Brundrit the ship builder and quarry

master. He was a staunch Anglican and yet his eldest son became a Roman Catholic priest. Dennis Brundrit’s house is surrounded by gardens and there was a large orchard. In 1850 there were three large houses in the vicinity; Mr Cooper’s Grove House, Charles Hazlehurst’s Waterloo House and Dennis Brundrit’s house. Grove House has a Victorian front on it now, but you can see evidence of Georgian work on it. They were like three riverside villas on a country lane, how times have changed!

This is Roy Gough’s picture taken for me of the lock on the churchyard gate when the new extension was made to the churchyard. Donald and Bankes were the church wardens in 1833. It’s a very nice picture.

The ancient sundial, with an octagonal shaft. The sundial has long since gone. It was not the practice to erect gravestones in churchyards until about 1600. The oldest one in the churchyard, by the way, has the date 1622. The sundial is still there. That and Vicar Barclay’s stone are the only two still standing up there.

This is Archdeacon Alfred Maitland Wood, who was vicar from 1887 to 1911. He is seen at the door of the old vicarage. He was chairman of the Runcorn School Board for many years.

Archdeacon Wood, with a parishioner in the vicarage garden, about 1905; a wonderful top hat. This is one of Mr Mack’s photographs; I’ll talk about him in a moment. He was a very good photographer and this is one of his pictures. This picture was given to me by a friend who is here tonight. These are the bell ringers, hand-bell ringers, at the Parish Church. There was a certain amount of social activity. The Parish Church had hand-bell ringers then, about 100 years ago. In 1901 the church leased a house in the Georgian terrace opposite. The building was bought 10 years later and it served as the social centre of the parish for nearly a century. It became the parochial rooms for PCC meetings, concerts, cubs, scouts, guides, pensioners, magic lantern lectures, bazaars, Church Lad’s Brigade; you know the kind of thing. The Guild of St Mary, the Guild of All Saints held their meetings there. My rounds of talks began there. I used to use slides in school, and the children talked out of school. The next thing I know I got an invitation from the Guide mistress from the Parish School; would I like to show some slides to their Guides because they were going to sit for their local history badge? You know they wear badges all over. One of the badges was for local history and I went. The next week it got round and the parishioners of the parish invited me to talk, and so it became a non-ending show which carries on to today.

During the First World War the large vicarage house in Highlands Road, together with a couple of army huts erected in the garden,were used as an auxiliary military hospital. Hundreds of lightly wounded soldiers were treated there. Many local ladies volunteered to act as nurses. Canon Howard Perrin was the honorary chaplain. You can see him there in his army uniform in the middle of the picture. He was awarded the OBE for his services, the first to be awarded it in this area. Notice the occupational therapy, the mat making on the front row. The photograph was taken in 1917. The army huts in the vicarage garden were removed to Cooper Street, to the Cooper Street Mission, some of you will remember it. That closed in 1958.

A gravestone in memory of Solomon Shepherd, the industrious sexton, in the early decades of the 19th century. He was also the town crier; he was the bell ringer and the grave digger. The inscription reads “The world has, at various times, lamented the loss of eminent statesmen, divines, physicians, and otherwise men, but the parish of Runcorn has to lament the loss of one who executed his office faithfully”. Solomon Shepherd’s descendants still live in Runcorn.

These curious fragments were left after the demolition of the old church. They were left in the churchyard; one is the capital from an old column, and there is a keystone, which bears the date 1755. They have gone now, but an architect named Rickman, the man who first categorised the styles of English architecture, visited Runcorn and the only thing he found that was outstanding was a very finely sculptured capital, I wonder if this could have been it? I don’t know, it’s gone now.

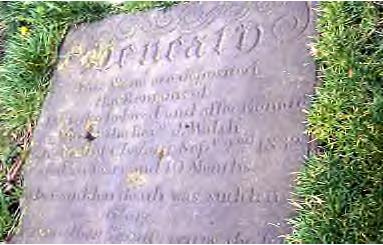

When you go in the churchyard again, go to the north door on the riverside and you will find the grave of Jane, the wife of the Reverend John Walsh, who died of cholera on September 2nd in 1832. As you can see there is the word cholera on the gravestone, in the middle line. Her fourteen month old son died of the same disease a couple of days later. Cholera claimed John Dunn the surgeon and you will find his gravestone in a part west of the church. Eighteen people died of cholera and twice as many more were infected with it. Terror in the town. The scourge was felt all over Britain; thousands died of it in the mid 19th century. It was ended by the industries of Runcorn and Widnes which produced bleaching powder, which is a powerful disinfectant, and it was used to disinfect water supplies. Cholera died out in Britain from then on. This bleaching powder was not only used in bleaching, but was sent all over the world to purify water supplies. My father served in the First World War, in Mesopotamia, Iraq, or Palestine as they call it now, and one of his jobs, his only job, was purifying water supplies, and homesick, tired and weary he sat down on a box one day. He turned it up and there was this label stating “manufactured in Widnes”. A long time ago, in 1917.

A fragment of a medieval gravestone found in the demolition of the old church. One was found intact, I don’t know what has happened to it. It was of Sir Richard Aston, of Aston, and his wife Matilda, who died in 1400.

Roy Gough did a circus act for me to try and photograph a mouse that lived in the stiff leaved foliage of one of the capitals. Now, he said he saw it, but I can’t see it. The last vicar, Mr Thomas was looking for it for years, but never found it. But, somewhere in there, allegedly, was a mouse, a stone mouse. It was a play of light and shade, I think.

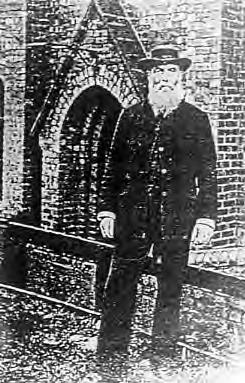

William Shaw, of the Mersey Mission for Seamen, Shaw’s Mission, which was closed after the war. It was, of course, an Anglican foundation and reports of his activities were in the parish magazines of the time. The building finished its life as a workshop for the college of further education. If anyone deserves to be remembered, it is this man. From 1875 until his retirement in 1921 he operated the Seaman’s Institute in Station Road.

A true, worthy Christian, who deserves to be remembered, he spent his life working with poor seamen and narrow boat people. He was so respected he was always referred to as ‘Captain Shaw’ and his mission was known as ‘Shaw’s Mission’. It was an Anglican foundation, as I say.

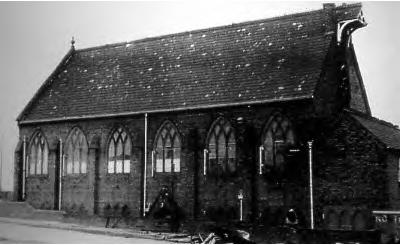

The Parish School with Gothic windows on the ground floor which were changed in later years for more efficient lighting. The old Parish School, of 1811, built by Mr Keyt, Vicar Keyt, was the first of Runcorn’s schools. It grew so quickly that Mr Keyt’s original school had to be pulled down and this one dates from 1833.

A detail from the old church school façade has been saved to grace the entrance to the present school. The provision of elementary education in Runcorn pre-dates the Educational Act by over 60 years; the churches were providing education 60 years before the Act of 1870. I’m glad they saved that bit. Shaw’s Institute: its last job was to serve as a workshop. After the war there was little traffic coming into Runcorn Docks, there was no need for it, so it closed down. Mr Shaw died in 1926.

This is one of the chapels of ease within the parish of Runcorn.Aston Church was originally a chapel of ease to St Bartholomew’s, as the parish church was then called, and it was wrecked by bombs in the November of 1940. The restoration was not complete for another 10 years, yet duringthat time open air weddings were held in the church because there was no roof. Many of the plaques and memorials have been pieced together like jigsaws and put back on the walls.

Another Chapelry,(below,right) St Michael’s: the architect’s projection, this is how he intended it to look. Of course the tower and the spire were never built. It would have been fine it they had, you know.

Shaw Street School, one of Mr Barclay’s efforts, in the new town. Runcorn was hemmed in originally between the river and the Bridgewater Canal. When it began to grow and the cemetery became into being it expanded across the Bridgewater Canal into an area called ‘New Town’ - Shaw Street, New Street, that area - and this school was built to cater for the people in these new streets. Within 10 years it had to be increased three times in size because of the demand for education. This week one of the later headmistresses of the school died, Miss Mack, a delightful personality. My wife worked for her as a supply teacher. She really was a lady and her father was a distinguished photographer. I talked to Miss Mack about him, she said he wasn’t a professional, but I think he must have been. He couldn’t have been as good as he was, a brilliant photographer. The earliest record of Runcorn was due to Mr Mack’s pictures taken at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century. That school’s gone, of course, it’s hard to find out where it had been.

Another church was the chapelry of Christ Church, Weston Point, designed by Edmond Sharpe, a distinguished Victorian architect who designed three Watermen’s churches, sited along the River Weaver – Holy Trinity at Castle in Northwich, and Christ Church at Winsford. Christ Church at Weston Point is now redundant, a listed building. The Vicar of Runcorn had overall responsibility for this church. It’s now the only building left standing in the dock area. The photograph is believed to be a celebration of Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee in 1897. About 10 years ago the last service was held, then the door was bricked up and the windows were heavily boarded to protect the church against the weather. A few months ago a Commission from Redundant Churches went in to see that all was well and they found that all the church furniture had been stolen, including the font, then it had to be bricked up again. You see, Weston Point docks were abandoned; no one is there, no safety measures, so it was done by talented thieves obviously.

All Saints spire, another one of Roy Gough’s pictures - a beautiful picture. It was originally 161 feet tall. It had a weather vane, which was removed some time ago. It’s got a square tower and an octagonal steeple, very impressive. The clock was made by Hanley of Runcorn. As I said to you before, the tower has a peal of eight bells, and yet they are rarely rung now. I believe they are on a Sunday morning. There was a time when the bell ringers used to practice on a Tuesday night. Now, I lived in Widnes and I worked in Runcorn and I was going home one night along Mersey Road to Widnes on the Transporter, when a voice from heaven called “Mr Starkey”, I looked up and the church was surrounded by scaffolding and on the top, the very, very top, there was a young man working. I taught him a few years before, a real rough diamond, a wonderful kid, and he waved to me and I waved back. Then, to my horror, he did a handstand on the very top and as I wobbled my way to the Transporter I could hear his laughter following me. Remarkable isn’t it? He was probably quite safe, but oooh! So, it was a score to him really, settling old scores.

This is a winter viewof the church. Strange to say that although there was a vast trade in Welsh roofing slates into Runcorn Docks, the original roof was of Westmorland slate, slightly greenish, heavy slate. A few years ago the iron nails holding them into position rusted away and the whole roof began to shift. Something had to be done and the roof was repaired using copper nails, very expensive copper nails, I remember seeing them in the grounds. Strange to say there is no sign of erosion on the church. It must have been made from the very best quality Runcorn sandstone, which hardens after being cut, in the atmosphere. But, Halton Church, probably built of Halton stone, the erosion caused by the ferocious Victorian winters and by the pollution of a century has eaten away all the drip stones. They have all fallen off, as have the mouldings around the church. The damage that has been done has been patched up with cement patches here and there, but here, apart from a few little cracks above the east window, there is no sign of erosion on the church. The roof timbers were imported from Memel in Lithuania, they are fir and I understand that the interior furnishings are of American oak.

A summer scene,(right) a delightful picture, Canon Barclay’s grave is just to the corner at the bottom of the tree. The doors are massively constructed in time honoured tradition when churches were used as places of refuge against marauding robbers and war parties. Often there were no other substantial buildings so the church had to serve as a castle really. The doors of the Parish Church are constructed of oak planks, some vertical and the other oak planks are horizontal, kept together with heavy iron bolts. Only the south door, the one seen here, is used today. They say the big west door that you can see from Waterloo Road is occasionally opened, but I’ve never seen it open. The north door’s fused to, it’s never opened. These pinnacles are 50 feet high and they are a prominent feature of this church. Now, I’m not making a claim that All Saints is a great architectural treasure, it’s not. I looked it up in his book of ‘Buildings of Cheshire’; Nicholas Pevsner, the famous art historian, does not condescend to comment on the building, but there is very little else of good architecture in Runcorn and I am sure that you will agree it’s a worthy building and certainly enhances the town. A most conspicuous landmark, a very impressive building I think. It’s got a long history; it’s been the centre for Christianity for nearly 1,100 years.

Another summer view.(left) The large parish of Runcorn was much reduced when the long connections with the ancient chapelries were severed in mid-Victorian times. A new parish of Holy Trinity came into being in 1841, carved out from Runcorn parish. St Mary’s, Halton, became independent in 1860, Aston, St Peter’s in 1861, Thelwall in 1870, and Daresbury in 1880. St Peter’s Mission used to be a parish in the Dukesfield area, but never came into being because the Bridgewater Navigation Company refused to allow a permanent church to be built in the area. Of course, All Saints was much reduced again when, in 1931 St Michael’s and this parish here where we are meeting, St John’s, Weston, came into being.

In the last slide, a view from Mersey Road. The spire and the pinnacles present striking silhouettes against the western sky. This is perhaps my favourite view of the church. My photograph doesn’t do justice to this view because I failed to get the interesting ‘spiky’ silhouette that I was trying to get; I’ve only got two pinnacles against the skyline. But if I’d gone further up towards Old Quay I’d have got a better picture, but do look at it some time; against the evening sky, the spikiness of the church is quite striking. That’s it – thank you for listening.